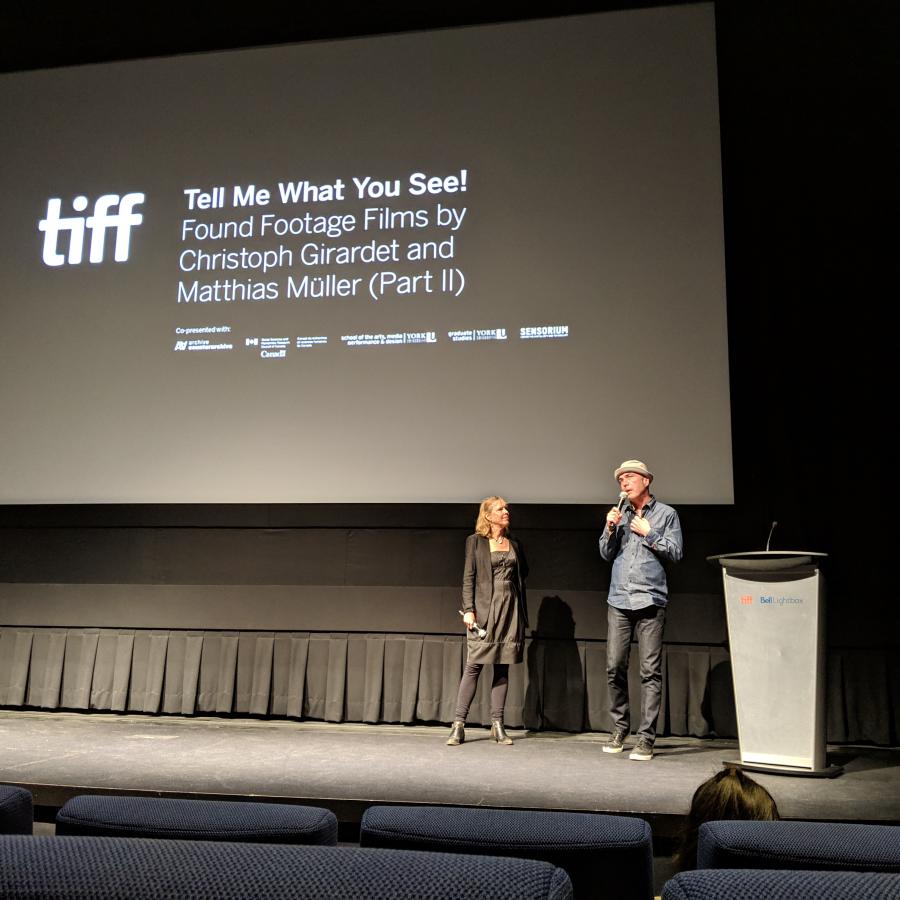

A/CA's Summer Institute featured a Master Class at York University with German experimental filmmaker Matthias Müller, as well as two programs at the TIFF Bell Lightbox featuring his found footage film works with long-time collaborator Christoph Girardet. The first program consisted of earlier collaborations, and was introduced by Scott Miller Berry. The second program featured more recent works, followed by an onstage conversation with Müller and Catherine Russell (Concordia University).

Read below for Scott Miller Berry's introduction to the first program on April 24, 2019:

Good morning! Thanks for having me, I'm humbled to be introducing this lovely program of early works by Matthias Müller as part of the Archive/Counter-Archive project's 2019 Summer Institute at York University.

It's so lovely to watch movies in the cinema in the morning, right? We just don't do it enough... I like how it feels closer to dream state for me, but now you all know I'm not much of a morning person...

First thing's first, some facts: I'm here as a full-time film lover, part-time film maker; and full disclosure, without any art history or those kinds of credentials beyond my commitment to persistent watching and steadfast presentation of films and public programming through my cultural work.

If you'll indulge me, I'd like to set up a simple dichotomy with which to frame this introduction: known vs. unknown AND fact vs. speculation.

Here's what I do know: Müller was born in 1961 in Bielefeld, Germany which is in the northeast of the Rhineland, in the centre west of the country. He attended university in his small hometown to study art; and later went to Braunschweig for graduate studies. As an undergrad he co-founded "Alte Kinder" (literally "old children") with 3 classmates as a D.I.Y. distribution/touring collective to present their Super 8 films to a wider audience, and to meet other like-minded small gauge obsessed persons along the way....

Also factual: Since 1979, Müller has made over 35 films; since 1999 most are in collaboration with artist Christoph Girardet (you'll see their creation PHOENIX TAPES today; and the screening here on Wednesday, May 8th features more collaborative films by the two artists).

PHOENIX TAPES (Christoph Girardet & Matthias Müller, 1999)

Also known: Müller's films have been screened at festivals, cinemathèques and micro-cinemas large and small from Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Rotterdam, MOMA, the Walker, Image Forum in Tokyo; and the Images Festival, Pleasure Dome, and TIFF all right here in Toronto.

He has expanded his artistic practice to include photography and gallery installations. Like his films, these artworks often use found materials; in other words they "sample" from existing footage including Hollywood films, archival works, and home movies sometimes called "orphan" films.

What I don't know: what pushed Müller on this trajectory to interrogate the archives of human emotions imprinted onto film stock? I can only speculate about his creative impulses based on the films themselves and my personal responses...

I do know that when I first saw THE MEMO BOOK, the first film we'll watch together today, I was forever changed. I couldn't believe someone could capture such a range of human emotions in one motion picture: grief, rage, reflection, redemption. And shot on small gauge Super 8 film no less, and hand-processed with luminescent super impositions to boot. THE MEMO BOOK (27 mins) was completed in 1989 with footage from the previous ten years; Müller was compelled to create the work after learning a former lover had died of AIDS. He withdrew into his apartment to contemplate his own mortality; the film is a stunning exploration of flesh, mirrors, anonymity, disconnection, and ultimately of survival.

I could speculate on this penultimate diary film for days; while the film feels cathartic to me, I could be projecting my own sense of existential dread onto it. Isn't that what we're always doing while watching moving pictures in the dark? Trying to make some connection/s to what is appearing before us? THE MEMO BOOK is a stunning diary of searching and longing; of digging and discovery; of pain and healing.

Here's a short quote from Roger Hallas:

In the various hand-processed treatments undertaken on its image, THE MEMO BOOK displays an emphatic tension between the aesthetic expression of ephemeral states, like dreamwork and memory, and the stark reminder of the film’s materiality. By emphasizing the materiality of the film, Müller sets up one of its most striking metaphors — the film as body.

PENSAO GLOBO (Globe Inn) is the second film; it's from 1997 and is 15 minutes. For me it feels like a followup to MEMO BOOK in that it's a personal exploration of death. Rewatching it again recently after 20 years, I was simply awestruck by the colours - how did he achieve such depths? Such richness in the reds? It's like somehow Technicolor created a new double colour stock just for this film.

Speaking of double, PENSAO GLOBO is told through a series of stunning double exposures - as if there's a ghost story parallel with the story of the man, our protagonist, who has gone to the Globe Inn in Lisbon and is waiting to die. The double exposures are used to hypnotic effect - the man is watching himself while we are watching him; watching them. He's in fact turning the classic filmic representation of death on its head and giving us multiple perspectives on movies as in life.

This feels like a theme in Müller's films, how we watch and how we interpret cinematic representations. It's interesting that we never see the man's entire body, that is contrasted with archival footage and what appears to be a mother holding her young baby (actual home movies shot by Müller's father) over the lush red wash of a heart beating. I'll argue that the body is both intensely present and absent while a voiceover is taken from audio recordings of an HIV-positive patient.

I speculate about the film's association of public versus private: the man's private doom in the dark pension house contrasted with his walking the streets and gardens of Lisbon; the chambermaid's making and remaking of the room for temporary private stays; Müller's use again of found footage; this time a clip from The Incredible Shrinking Man... the line that stands out for me: "Sometimes it's like I'm already gone ... become a ghost of myself." For me that's an ideal metaphor for film, for moving images, and for our time limited lives: each frame, each moment is already gone by the time we've seen we've experienced it.

I'll end with a quote from the NY Film Festival: "Eight years after his elegiac THE MEMO BOOK, Müller revisits Lisbon, the city of fate, of longing and decay and divisible selves. Shadowing his protagonist from a hotel cell into labyrinthine streets, the film contemplates dissolution and the permeable boundaries between life and death."

HOME STORIES - the third film we'll see is from 1990; the film that followed THE MEMO BOOK and heralded as Müller's best known film. This six-minute tour de force is a compilation of clips from 1950's women in Hollywood melodramas; it's a dense dizzying array of archival clips that pull all of the emotions of a reaction shot together to create a moody mysterious drama all of its own. I'm in awe that a collection of existing clips can be edited together this smartly; it feels like a magical combo of horror comedy. I wonder what inspired this film, and what Müller might be trying to say about the roles of women and how they're portrayed in these films (and I would argue, continue to be portrayed). We see women framed here in dark doorways, hallways, windows and ornate architecture; expressing emotion that is never fulfilled or resolved; yet through the precise editing, their stories become a new narrative altogether. Here's a quote:

HOME STORIES proposes a complex aesthetic quality that lies between various different realms of representation: the autobiographical, the political, and the semiological [...] The strength of Müller’s intervention does not only reside in his underlining of the conventions linked to American culture but also in his proposition, as an alternative, of another film which gathers together these figures in a sort of melancholic choreography. By manipulating these archives, he is in effect rewriting his history of cinema in a slow symphonic progression, in memory of all those lost moments.

HOME STORIES (1990, MATTHIAS MÜLLER)

PHOENIX TAPES is the fourth and final film today; it's from 1999, Müller's first collaboration with Christoph Girardet and is 45 minutes. The film was commissioned by the Oxford Museum of Art for a Hitchcock exhibition on the centenary of his birth.

It's a dizzying collection of clips from 40 Hitchcock films, articulately arranged into six parts - revolving around LOCALES, OBJECTS, TRAINS, MATERNAL RELATIONSHIPS, BEDROOMS, and DEATH.

I find the film to be nothing short of liberating - we're confronted with Hitchcock's tropes, obsessions, techniques, iconographies, but distilled down into a dense hypnotic collage... for me, it pulls all of the dread and fear from the films right into the forefront. It's the perfect film for our Instagram days, in my humble opinion, and for the ARCHIVE/COUNTER-ARCHIVE project to kick off its York Summer Institute - let's close with a far more articulate quote from Dana Lissen:

PHOENIX TAPES consists of a de/reconstruction of fragments from 40 Hitchcock films, arranged in six parts. It is a homage, as well as a forensic and psychoanalytic investigation into the optical unconscious of Hitchcock’s work; a work that shows how necrophiliac film-loving can be, but also that there is a desperate Dr. Frankenstein hiding in each cinephile, who keeps on trying to breathe new life into the cinema. What do these films tell us – about film, about Hitchcock, about their own stories, about the time in which they are made – about what they don’t know themselves? Hence they expose the underlying structures and patterns – vulnerable in all their nakedness. But also frightening because of the way in which this dominant Hollywood narrative makes us fall in love with dead stars, and conditions us in our thinking about family relations, role patterns for men and women, gender and genre, the family as a mini society, power and manipulation, and the exclusion of the other.